What I’m Buying in This Dip

The market is fearful about AI. That’s when opportunities arise

Is the AI bubble losing air?

The AI boom seems to be fading, or at least that is what the market has been signaling over the last few weeks.

Here is how some of the largest and most AI-exposed stocks have been performing:

NVIDIA is down 16% from all-time highs

Broadcom is down 20% from all-time highs

AMD is down 24% from all-time highs

Oracle is down 45%

CoreWeave is down 63% from all-time highs

Nebius is down 43% from all-time highs

We are not yet at crash levels, but if there is a bubble, it is clearly losing air.

The debt markets are not sending a more optimistic signal. In fact, they appear to be pricing the current trend with increasing skepticism.

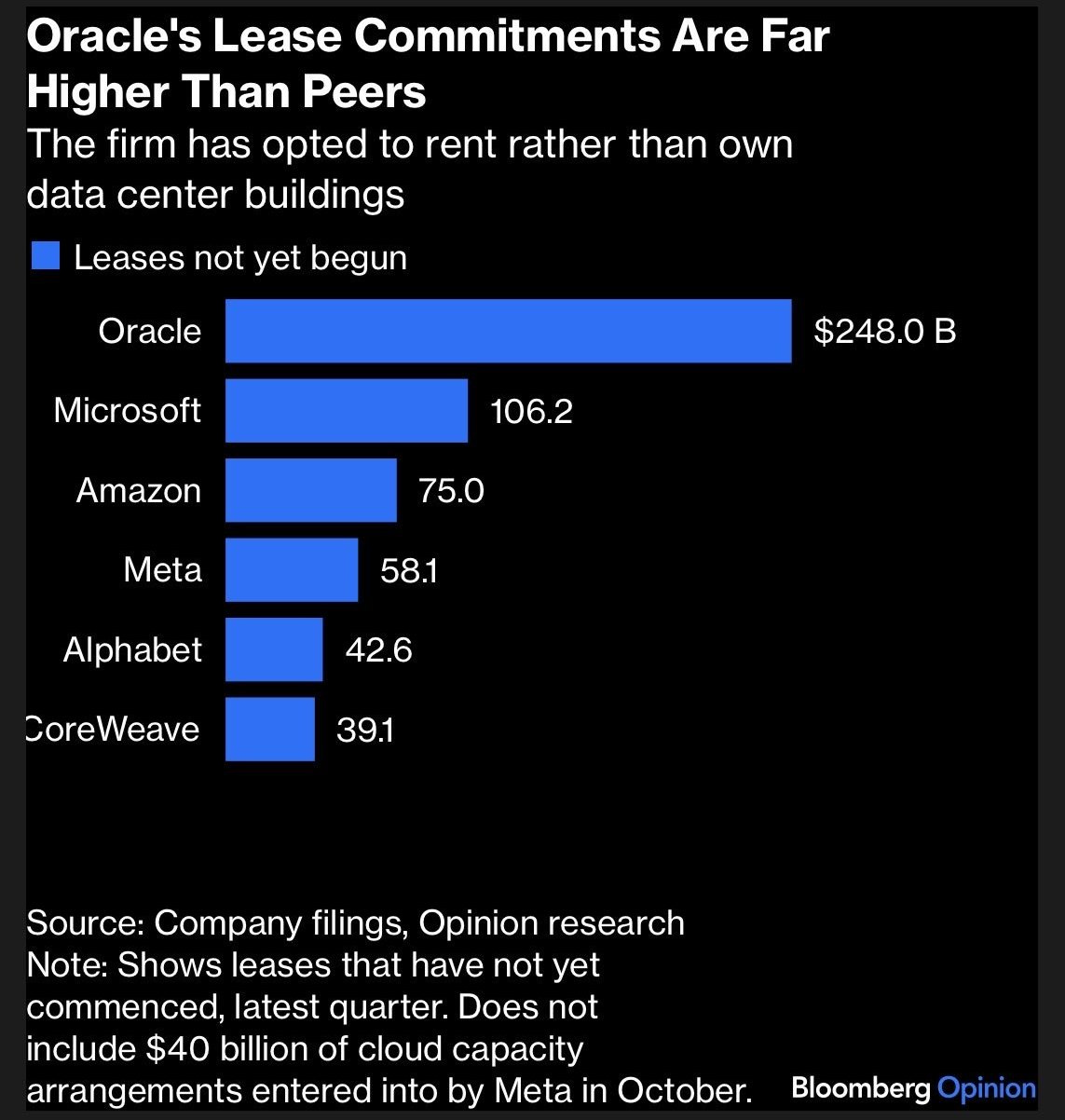

The case of Oracle

Oracle’s credit risk just hit its highest level since 2009 following earnings. $ORCL credit default swap spreads have widened sharply, moving from 55 basis points to 124.6 basis points in just three months. This implies a five-year default probability of roughly 9.2%.

Oracle is among the tech giants borrowing aggressively to fund artificial intelligence data centers. Banks involved in construction loans tied to Oracle have been buying credit default swaps on the company’s debt to hedge their exposure.

Investors and hedge funds have also increased their hedging activity amid concerns that rising leverage is weakening Oracle’s credit metrics and could eventually push the company into high-yield status.

The bear case by IBM

Headlines are starting to point in the same direction. The IBM CEO recently stated there is no way that spending trillions of dollars on AI data centers will pay off at today’s infrastructure costs. At roughly $80 billion per 100 gigawatts, this implies a total computing commitment of about $8 trillion.

It is my view that there is no way you are going to earn a return on that, because $8 trillion of capex would require roughly $800 billion of profit just to cover interest costs, he said.

However, this reasoning is unnecessarily catastrophistic.

For starters, hyperscalers’ new long-dated USD bonds are currently being priced with an average 5% coupon across Amazon, Microsoft, Oracle from its September issuance, Meta, and Google. That is far from the 10% interest assumption embedded in this argument.

Second, the hypothetical $8 trillion of capex is not a lump sum. Hyperscaler capex, including AI-related spending, is projected to average roughly $400 billion per year in 2025 and over the following three years. At that pace, reaching $8 trillion would take around 20 years, not an immediate surge.

Now consider a broader perspective that goes beyond hyperscalers and OpenAI and looks at overall data center demand. According to 451 Research, estimates for U.S. data center utility power demand show the following trajectory, as cited by S&P Global:

Demand rises by about 11.3 GW in 2025, reaching 61.8 GW by year-end

It increases to 75.8 GW in 2026

It reaches 108 GW by 2028

It climbs to 134.4 GW by 2030

That implies an average increase of roughly 14.7 GW per year. At that rate, it would take nearly seven years to reach 100 GW of data center investments.

This context matters. Once the numbers are laid out, AI infrastructure investments do not look nearly as aggressive or reckless as some critics suggest.

Most importantly, the IBM CEO also stated that AI is likely to unlock trillions of dollars of productivity across the enterprise. He added that achieving AGI will require more technologies than the current LLM path.

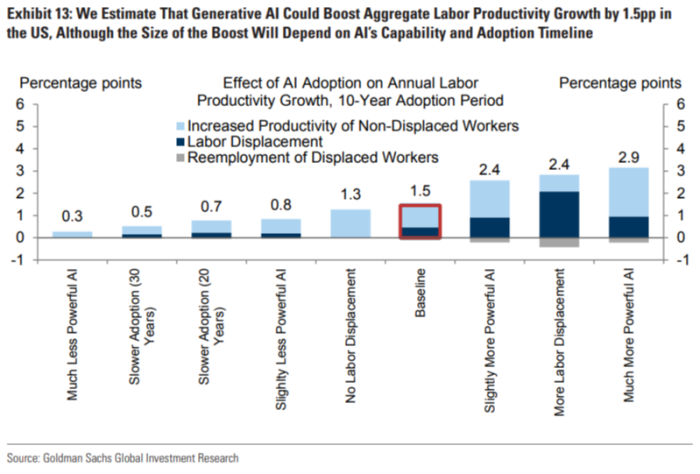

If AI can indeed unlock productivity measured in the trillions, it becomes difficult to argue that an $8 trillion investment, spread over many years, is unjustified. Even applying a very modest multiple to that incremental productivity, the economics start to look compelling.

In the end, not even Arvind Krishna appears fully committed to a bearish stance. On one hand, he highlights an extreme capex figure. On the other, he later stated that he does not see a bubble. His skepticism seems less focused on data centers themselves and more directed toward the software and GPU layers.

On that point, there is some agreement. Not every company building AI models will succeed, and consolidation in that segment should be expected.

Although I believe many companies will develop niche AI models for specific use cases, as we have already seen with Tempus AI in precision oncology, Tesla in autonomous driving, and Figure AI in humanoid robotics, I also think it is true that the generalist LLM market will end up far more concentrated than social media, largely due to limited differentiation.

Not a winner takes all market

Today, there is still a rationale for using different models. Claude tends to perform better at coding, ChatGPT at general reasoning, and Gemini at image and video generation. Over time, however, these gaps are likely to narrow.

When you look at a company like Meta, which is spending hundreds of billions on a relatively disappointing product like Llama, it becomes easier to see why some players may not end up as winners in the generalist LLM race.

That does not mean Meta is destined to fail. The company can still generate strong returns by applying AI to its existing platforms, as it already does on Instagram through automatic translation, lip-syncing, and AI-powered advertising.

The key point is that these gains could likely be achieved with far lower investment, and abandoning the ambition of building a proprietary frontier LLM may actually be the more rational strategy at this stage.

The market would likely overlook extraordinary costs, such as $100 million signing packages for top AI engineers or even $100 billion investments, if they resulted in best-in-class models. What is harder to justify are massive expenditures that produce an underperforming model used by enterprises primarily because it is open source and free.

It is reasonable to see signs of overspending when focusing on the software layer of AI. More than AI itself being a bubble, the real risk lies in individual companies becoming overhyped and allocating capital to initiatives that may never generate adequate returns. That does not necessarily imply broader damage to the overall market.

Notably, the IBM CEO has not expressed concern about the hard assets underpinning AI. His view is that even if some software companies fail, the eventual winners will still rely on the same data center infrastructure, ensuring that this capacity continues to be utilized.

His main capex concern, similar to Michael Burry’s, is GPU depreciation.

What if we’re spending too much on GPUs that only last 3 to 5 years?

As I covered before, if the productivity returns are actually going to be in the trillions, then every penny is well spent. That is only true if you are going to be a winner. If you are spending hundreds of billions on GPUs that you will not put to good use because you are not leading the race, it becomes a bad investment. As long as we are talking about winners, these investments will pay off. In fact, they are paying off today.

As I have covered in my past data center articles, these deals are tremendously profitable for companies enduring GPU depreciation like Iren and Nebius, even when using very conservative assumptions on schedules and residual value. At the moment, the economics make sense at the data center level. The question is whether they will also make sense at the model level.

OpenAI

As we all know, OpenAI is making plenty of leasing commitments with money it still does not have. According to Reuters, OpenAI is on track to generate about $13B in top line revenue this year, while burning roughly $8.5B in cash. Their leasing commitments for compute exceed $1.4T over the next seven years.

That includes $250B for Azure services over an indefinite period, $300B of Stargate related investments over the next five years, $38B committed to AWS over the next seven years, $23B in contract value with CoreWeave over the next five years, as well as commitments to deploy 6 GW of AMD systems over the next five years and 10 GW of Broadcom ASICs. That comes out to roughly $200B per year in commitments, potentially a bit less if there is some overlap within the broader Stargate project. I did not include their 10 GW NVIDIA GPU deployment, already assuming overlap.

Can OpenAI pay for all of this?

OpenAI has had the fastest run rate from $0 to $20B in revenue in the history of tech. While that figure looks small compared to their investment commitments, it is worth noting that the AI cycle, just as happened with compute, is front loaded into data centers and infrastructure first, because demand for the end product already exists.

Once those investments are made, monetization tends to come at an exponential rate.

Because of that, comparing OpenAI’s current revenue, supported by much lower capex, to its future capex and lease commitments is misleading. These commitments are gradual, with a ramp over several years. They start lower and increase as capacity scales. This structure allows OpenAI to keep growing, and as it grows, funding the next phases becomes easier.

How much can they grow?

The productivity gains of AI

That is still unknown, because these buildouts will unlock capabilities never seen before, making them impossible to study historically. What we do know is that AI is already delivering meaningful productivity gains where it is usable.

In a preregistered online experiment, MIT researchers Shakked Noy and Whitney Zhang found that using ChatGPT for professional writing tasks cut completion time by about 40% and improved output quality by about 18%.

In a large real world study of 5,172 customer support agents, Stanford and MIT affiliated economists Erik Brynjolfsson, Danielle Li, and Lindsey Raymond found that a generative AI assistant increased issues resolved per hour by about 15% on average, with larger gains for less experienced workers.

In a controlled experiment on developer work, researchers found that developers using GitHub Copilot completed an HTTP server task 55.8% faster than the control group.

A Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis analysis reported that GenAI users saved 5.4% of work hours on average in the prior week, equivalent to about 2.2 hours per week for a 40 hour worker.

A large scale UK Civil Service evaluation of Microsoft 365 Copilot reported an average of 26 minutes saved per day, translating to roughly 13 working days per year.

A field experiment documented by the Bank for International Settlements found that Ant Group’s coding assistant increased code output by more than 50%.

The productivity gains are there. Now it becomes a question of adoption and the expansion of new products.

There are countless use cases beyond what AI is used for today. AI agents will push AI from being a tool to acting as a worker. More capacity and next generation accelerators will reduce cost per token. If LLM providers keep subscription prices stable while capabilities improve, this can drive significant margin expansion.

Lower costs and more capacity also reduce time per task. If time per task is the main constraint on output today, scale alone can unlock much higher productivity. Improvements in memory will allow for longer tasks, wider context windows, and expanded use cases in video creation, image editing, complex coding workflows, and many other reasoning tasks.

Judging AI based on what it is today, while judging investments based on what AI could become over the next decade, creates a distorted and biased picture.

OpenAI’s Financing

Even if AI delivers the productivity gains these plans imply, AI labs will take years to become consistently profitable. Financing will therefore require more than revenue, relying on equity and debt.

The most recent confirmed valuation for OpenAI is $500B, set by a $6.6B secondary share sale that closed on October 2, 2025. In March 2025, OpenAI announced a $40B funding round at a $300B post money valuation, led by SoftBank with participation from Microsoft, Coatue, Altimeter, and Thrive. In September 2025, OpenAI and NVIDIA announced that NVIDIA intends to invest up to $100B, deployed progressively as each gigawatt comes online, with the first 1 GW targeted for 2H 2026.

Altogether, this amounts to roughly $50B raised in a single year, a valuation increase from $300B to $500B, and a $100B capital commitment tied to deployment. This still falls short of the roughly $200B per year in average capex and lease commitments over the next seven years, but it is a strong start. OpenAI has also not meaningfully tapped credit markets, which remain an option.

Where things could go wrong: OpenAI clearly loses leadership

Claude has already surpassed OpenAI in API revenue and code focused products, while OpenAI still leads in consumer and overall business revenue, reinforcing the idea that different models can dominate different segments.

As long as OpenAI keeps leading in consumer and business subscriptions, they will be able to raise capital, grow, and keep the AI machine compounding.

Now, there is another big player, and that is Google.

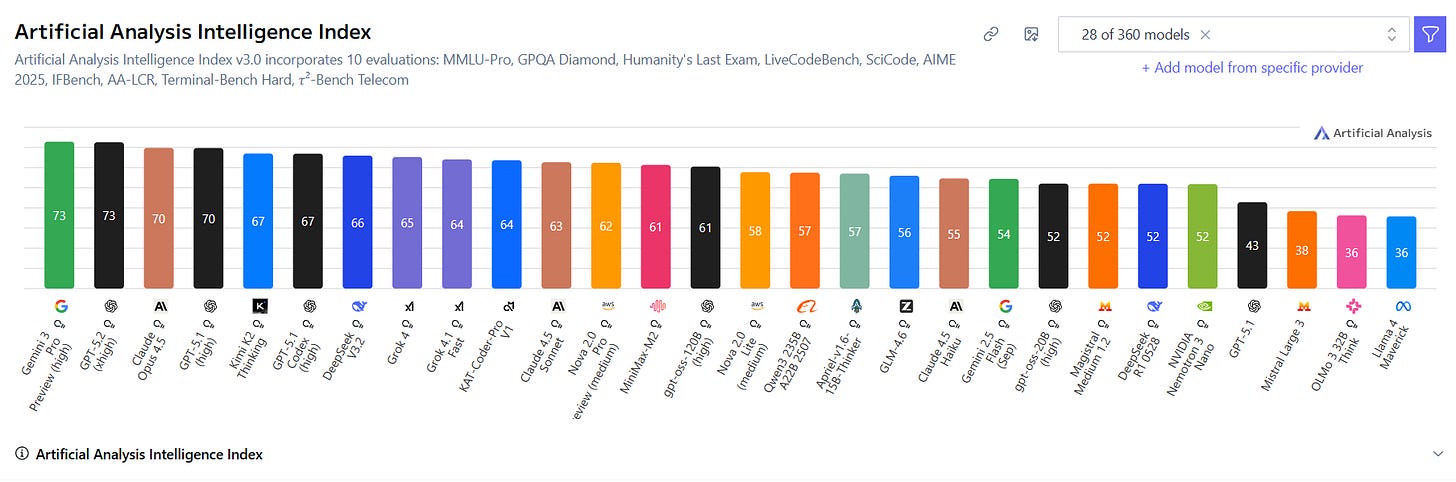

According to the Intelligence Index by Artificial Analysis, Google’s latest model is on par with OpenAI’s.

This wouldn’t be as much of a threat to the OpenAI empire if it weren’t because Google uses its own AI accelerators, called TPUs.

Suddenly, there is clear evidence that you can achieve the same results as with NVIDIA GPUs, without using any of their hardware or software.

What happens if Google wins?

Even in a worst-case scenario, it’s not likely that Google would be able to outperform OpenAI by a wide margin. It hasn’t happened so far, and generally OpenAI has held the lead, so while Google could gain a small edge, a landslide win seems unlikely.

Now, given that Google uses its own ASICs, called TPUs, co-developed with Broadcom, there is a possibility that it could squeeze OpenAI’s margins to the point where the business becomes financially unsustainable, or at least force OpenAI to walk back commitments.

Google not only avoids the NVIDIA markup on both hardware and software, but can also deploy on its own terms. On top of that, it has a core business generating roughly $150B in operating cash flow per year, meaning Google can scale its AI data centers without relying on equity or debt raises.

The Data Center Thesis

This is why data centers are one of, if not the most de-risked investments at the current stage of the AI supercycle.

We do not know if OpenAI will fail to gain and maintain leadership again, or if Google will end up forcing them to scale back because they cannot secure the financing they need. What we do know is that whoever wins will need data centers.

Google is already quietly building a network of connections with data center operators across the US, supporting deals through its Fluidstack partnership with Cipher, TeraWulf, and now Hut.

Data centers are not just protected because every major AI player needs them, they are also recession-resistant. If there were an AI winter, or even a broader recession, GPU demand would likely collapse. Many GPUs would sit idle or be priced far lower, creating significant financial stress for anyone that bet too aggressively on compute hardware.

That is not the case for data centers, particularly those with secured contracts. Companies like Nebius, Iren, and the operators mentioned above have locked-in cash flows through long-term deals with hyperscalers. This gives them a premium position, not only in winning new deals, but in de-risking their balance sheets.

These companies can now work directly with hyperscalers, build new infrastructure based on actual demand signals, and avoid overbuilding, ensuring there is a tenant for every site.

If we reach a point where data center growth slows materially and fewer deals are signed, these companies would likely suffer multiple contraction. However, they would not be stuck with rapidly depreciating GPUs weighing on the balance sheet, nor with heavy debt taken on to acquire compute assets. Instead, they would hold slowly depreciating infrastructure such as grid connections, substations, liquid-cooling systems, buildings, and fiber-optic connections, and simply wait for demand to return.

Unlike companies such as Oracle or CoreWeave, these operators carry meaningfully lower risk, with equal or greater upside.

CoreWeave’s revenue is almost entirely tied to OpenAI, while Oracle is committing tens of billions of dollars to hundreds of thousands of GPUs without owning most of the data centers they rely on.

My Picks

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Daniel Romero to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.